|

The Marketplace for Women Corporate Directors

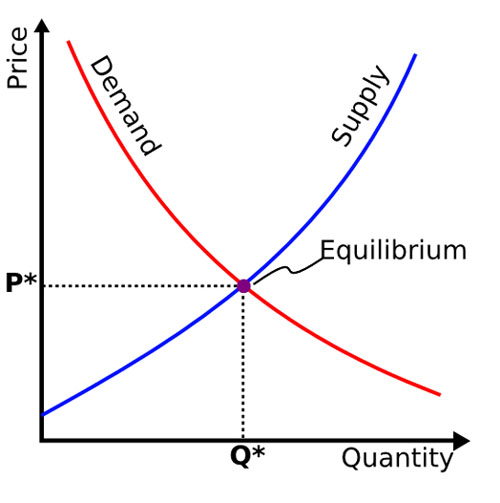

There is a marketplace where corporate boards of directors demand board members, both male and female. That marketplace also has a pool of candidate resources which we could call the supply of board members, both men and women.

Directors are selected, in part, from members of top management, specifically the 5 highest paid positions in major corporateions. Currently, women constitute somwhere around 6% to 8% of that top tier of management among the S&P 200 firms.

Corporate boards have managed to select women directors at over twice that rate: more like 16% of the independent director seats on boards at S&P 200 top tier firms, according to Spencer Stuart's Board Diversity Report for 2009. A significant majority of boards surveyed have stated that they are "looking for women and other diversity candidates."

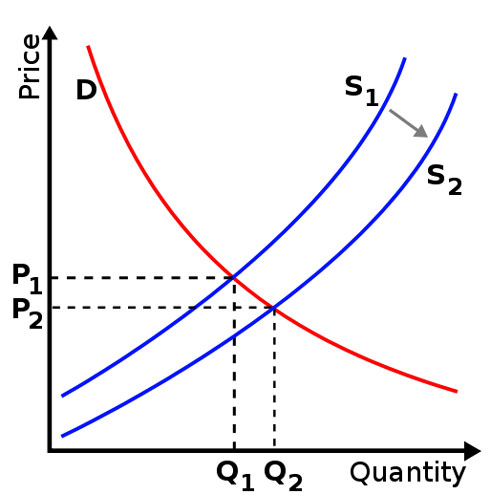

In basic economics, the supply-demand curves describe these two profiles. At their intersection, an equilibrium market price and quantity are said to result.

|

|

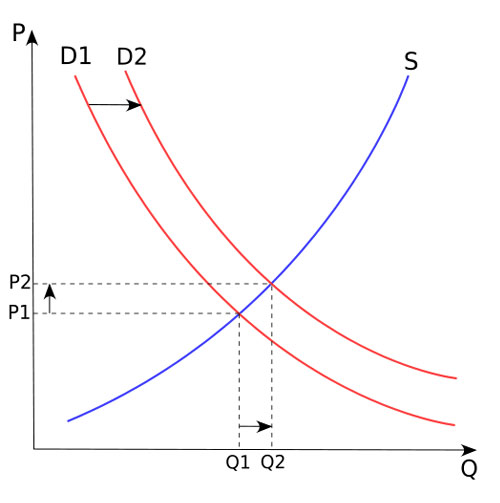

Boards of director have increased their demand for women (and diversity candidates) by reaching beyond corporate management ranks and conducting searches among academia, entrepreneurial firms, and consulting firms (finding law, accounting, and investment partners).

Under normal market circumstances, assuming an upward-tending supply curve, as boards pursue more women candidates, the demand curve would move outward from D1 to D2. The quantity of women tapped for boards would increase from Q1 to Q2, and the price would increase from P1 to P2.

This was the case in Norway when the country mandated a 40% quota for either gender on the boards at state organizations and ultimately public company boards of directors. The demand curve was pushed out, and women became a highly valued commodity. |

|

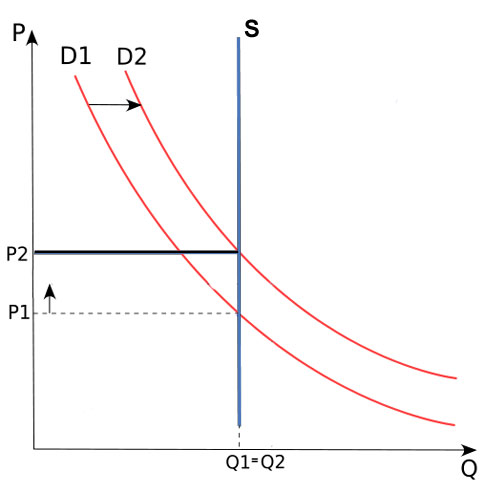

If the supply of compentent and experienced women capable of taking on top corporate board roles is limited, then the supply curve is not normal. Instead, it looks more like a stick figure. Supply is constrained, such that no matter how much demand and price are increased, little or no increase in the actual quantity results.

The supply curve describing the availability of women candidates for corporate directors is constrained: it is steep and inflexible, such that increases in director compensation in the post-Sarbanes-Oxley environment in the US have resulted in only small increases in the number of qualified women available to serve on public company boards.

Only the larger increases in compensation from P1 to P2 have resulted, with only small increases (if at all) in the quantity of female candidates from Q1 to Q2. |

|

|

In spite of efforts to increase the available supply of women director candidates through a major training program, Norway has experienced the severe adverse consequences of an excessively constrained supply:

- some companies delisted rather than comply; others went private, were acquire or merged, reducing the demand for directors rather than increasing it;

- companies reached into the upper management ranks and tapped women who were not quite ready, either in terms of age or experience; companies lost that executive talent before it could be fully developed experientially; boards ended up with directors not quite ready to perform at peak levels in public company governance; companies saw shortages of talented women in their top ranks;

- some companies reached into the European market to find experience women for their boards, infusing Norwegian companies with non-Norwegian governance experience (for better or worse);

- a few top women directors doubled and tripled their board service: 70 select women reportedly now serve on over 300 boards;

|

Women on board advocates, in the US and internationally, suggest that boards of directors must continue to move the demand curve out further in order to achieve the goal of increasing the number of women on top corporate boards of directors. This gets harder and harder to do as the number of women in the top 5 levels of corporate management continues to be limited.

If the US adopted the strategies of Norway, it would be a step backwards toward the "diversity quotas" that existed in the 1970s and 1980.

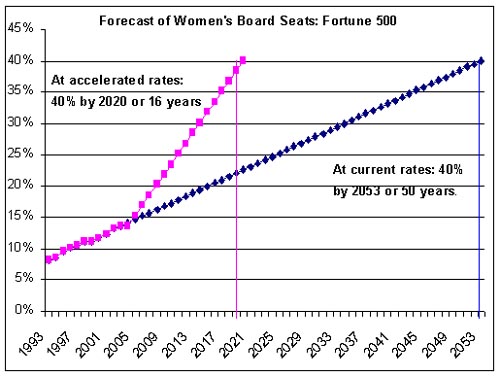

If the US followed the Norway example, it would mean a reversion to the days when women directors at Fortune 500 firms held an average of 1.5 director seats each (in the early 1990s) rather than the current average of 1.1 director seats per women. Over-boarding has been identified as a negative governance indicator in today's economy because directors are now required to invest significantly more time per board per year to address the more complex issues facing corporations.

|

|

A more viable alternative is to focus on strategies that increase the total supply of women director candidates from which boards can select talented and competent colleagues. This implies that the supply curve must become more normal and less constrained: we need more women available at all levels of top executive positions.

In order to have a more normal supply curve, it is necessary to change the slope by increasing the relative number and value of top calibre women prepared to perform at top tier corporate governance levels.

Many women on board advocates "pooh-pooh" the idea that the supply of qualified women director candidates is constrained. The evidence suggests otherwise. Women continue to over-board themselves at non-profits; they do not form boards of directors for their own entrepreneurial firms; many "opt out" of corporate leadership; women network among themselves rather than mixed-gender professional associations; and finally, when women attend panels on corporate governance, they ask almost "naive" questions which reveal that they have not yet acquired the appropriate relevant experience or training.

|

|

As we succeed in increasing the supply, we would also expect to gain some price efficiencies. As we improve the variety of independently-minded talented and competent women from a full range of professional backgrounds, we provide greater choice to corporate boards.

Boards will not be the only entities to benefit from an increased supply of women competent and prepared for leadership at the very top. Corporations will have a larger pool of top executives from which they may recruit. Civic and academic entities will have a larger supply of talent available to them.

A more normal supply curve means that there are women willing to serve at premium, middle as well as lower ranges in the price spectrum. This also means more choice for women candidates bidding in the marketplace.

One thing could not be clearer: over the long term, nobody benefits from distortions in the marketplace. Not Norway and certainly not the United States.

|

|

|

|

| |

|